T.J. Clark, The Painting of Modern Life

The Contemporary Case Against Haussmannization

The separate heads in the case against Haussmannization . . . can be rehearsed as follows. First, the business had been done wastefully and dishonestly. The empire was

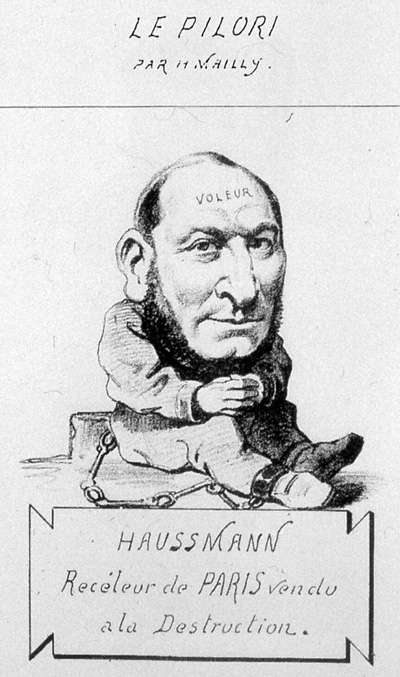

Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann, Prefect of the Seine, shown as a thief in a cartoon because of all the people who were displaced from their homes for his new Paris. |

in league with the speculators and the Haute Banque, and the baron had used his power to sell off the richest shares in the new construction work to the brothers Pereire and their unloved Crédit Mobilier [a bank supported by the Second Empire]. Boulevards and railways were all one in the opposition's eyes: things built too quickly, whose profits went to a secret few, and whose appetite for capital distorted the whole industry of France. The argument was only sharpened by its distance from the truth: in fact the profits of reconstruction had been spread quite wide, to the small proprietors grown rich on compensation, to the landlords making their fortune from inflated rents, to the swarm of men who fattened on the process of rebuilding and found a way to make money out of its side effects. The sight of such fortunes being made enraged those bourgeois who had not been richly expropriated or had somehow missed the chance to buy at the right time. What a howl went up in 1867 when the tinsmith from Fontanges, Lapeyre, was given the contract to demolish the pavilions of the Exposition Universelle [Universal Exposition – what we would call a world’s fair] and sell them off for scrap! He had caught Haussmann's eye originally in the auctions of rubbish from the slums; had been given key concessions: and when his son was married the baron had sent his card. It was all favours, kickbacks, and corruption, said those who wanted a part of all three.

Second, the city that resulted from this fever was supposed to be regular, empty, and boring. Haussmann had killed the street and the quartier; he had made instead "la CITE NEUTRE des peuples civilisés." [the neutral city of civilized peoples.] Once upon a time there had ''existed groups, neighbourhoods, districts, traditions" but all of them had passed away.'' There was no more multiformity in Paris, no more surprise, no more Paris inconnu [unknown Paris]. If the old bohemian Privat d'Anglemont, the man who had written the book of that name, could rise again from his humble grave at Montmartre, and ... indulge in one of those wild night-walks his spirit loved, he would lose his way at every step: he would be bewildered indeed before the College de France, and streets and alleys and wastes, which once had the Clottre Saint-Jean de Latran for their centre. Here were the headquarters of wandering Bohemians, street singers and conjurors, the vicious and the criminal and the unfortunate, all afflicted with the common curse of poverty. The Boulevards have broken through all.

''The straight line," need one say it, "has killed the picturesque, the unexpected. The Rue de Rivoli is a symbol; a new street, long, wide, cold, frequented by men as well dressed, affected, and cold as the street itself.... There are no more coats of many colours, no more extravagant songs and extraordinary speeches. The open-air dentist, the strolling musicians, the ragpicker philosophers, the jugglers, the Northern Hercules, the hurdy-gurdy players, the sickly snake-swallowers, and the men with seals who said "papa" -- they have all emigrated. The street existed only in Paris, and the street is dying...

Street Criers in the Old Paris (c1700)